On Monday, the Indian government released its latest estimates of economic growth for the last financial year that ended in March 2021. India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted by 7.3% in 2020-21. To understand this fall in perspective, remember that between the early 1990s until the pandemic hit the country, India grew at an average of around 7% every year.

There are two ways to view this contraction in GDP.

One is to look at this as an outlier — after all, India, like most other countries, is facing a once-in-a-century pandemic — and wish it away.

The other way would be to look at this contraction in the context of what has been happening to the Indian economy over the last decade — and more precisely over the last seven years, since the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led government just completed its seventh anniversary last week.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

Seen in this context, the latest GDP data suggests that it is not an outlier. Instead, if one looked at some of the most important variables in the data, India’s economy had been steadily worsening during the current regime even before the Covid-19 pandemic.

A worker unloads sacks of grain at a store in Chandni Chowk market in New Delhi.

A worker unloads sacks of grain at a store in Chandni Chowk market in New Delhi.

So has the Indian economy fared better during the seven years of the present government?

Perhaps the best way to arrive at such a conclusion is to look at the so-called “fundamentals of the economy”. This phrase essentially refers to a bunch of economy-wide variables that provide the most robust measure of an economy’s health. That is why, during periods of economic upheaval, you often hear political leaders reassure the public that the “fundamentals of the economy are sound”.

Let’s look at the most important ones.

Gross Domestic Product

Contrary to perception advanced by the Union government, the GDP growth rate has been a point of growing weakness for the last 5 of these 7 years.

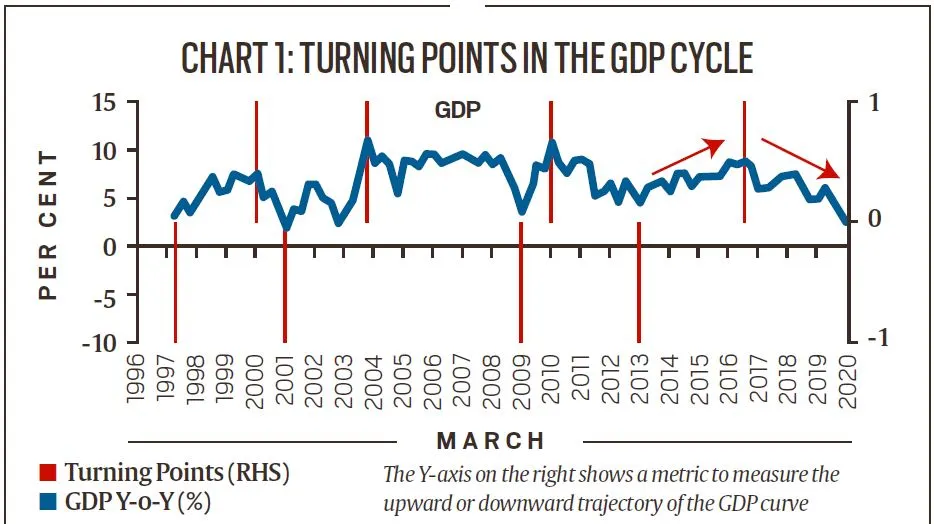

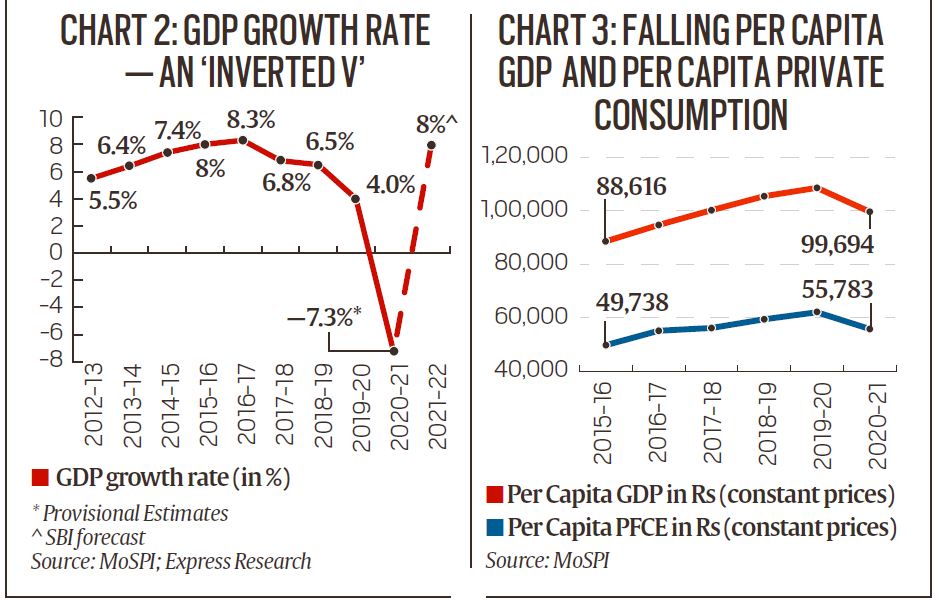

Let us look at Chart 1, provided in the Reserve Bank of India or RBI’s Annual Report for FY21 that was released on May 27. The chart maps the turning points in India’s growth story.

Two things stand out. After the decline in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, the Indian economy started its recovery in March 2013 — more than a year before the present government took charge.

But more importantly, this recovery turned into a secular deceleration of growth since the third quarter (October to December) of 2016-17. While RBI does not state it, the government’s decision to demonetise 86% of India’s currency overnight on November 8, 2016 is seen by many experts as the trigger that set India’s growth into a downward spiral.

As the ripples of demonetisation and a poorly designed and hastily implemented Goods and Services Tax (GST) spread through an economy that was already struggling with massive bad loans in the banking system, the GDP growth rate steadily fell from over 8% in FY17 to about 4% in FY20, just before Covid-19 hit the country.

In January 2020, as the GDP growth fell to a 42-year low (in terms of nominal GDP), PM Modi expressed optimism, stating: “The strong absorbent capacity of the Indian economy shows the strength of basic fundamentals of the Indian economy and its capacity to bounce back”.

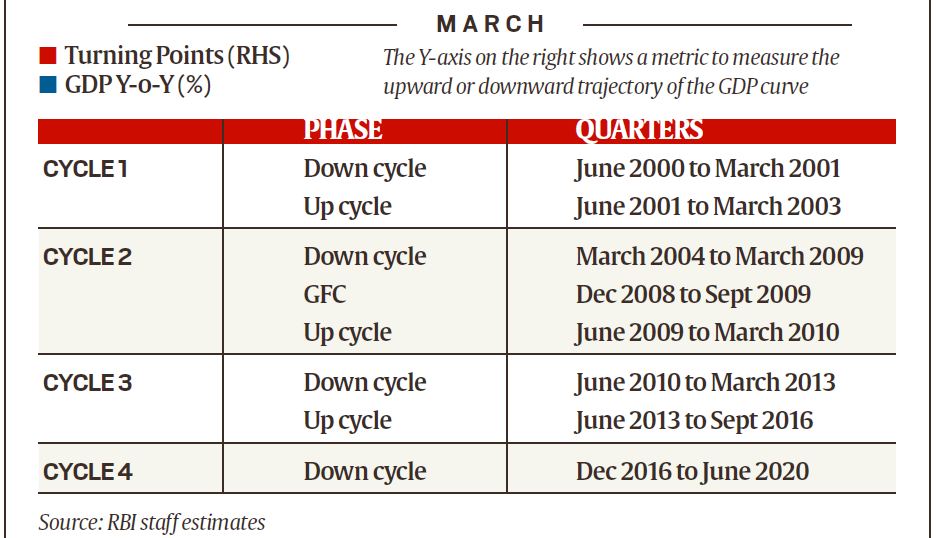

As an analysis of key variables suggests, the fundamentals of the Indian economy were already quite weak even in January last year — well before the pandemic. For example, if one looks at the recent past (Chart 2), India’s GDP growth pattern resembled an “inverted V” even before Covid-19 hit the economy.

GDP per capita

Often, it helps to look at GDP per capita, which is total GDP divided by the total population, to better understand how well-placed an average person is in an economy. As the red curve in Chart 3 shows, at a level of Rs 99,700, India’s GDP per capita is now what it used to be in 2016-17 — the year when the slide started. As a result, India has been losing out to other countries. A case in point is how even Bangladesh has overtaken India in per-capita-GDP terms.

A woman and a child exit a music store as a to-let sign is displayed on a floor below vacated by the tenant recently in Bengaluru

A woman and a child exit a music store as a to-let sign is displayed on a floor below vacated by the tenant recently in Bengaluru

Unemployment rate

This is the metric on which India has possibly performed the worst. First came the news that India’s unemployment rate, even according to the government’s own surveys, was at a 45-year high in 2017-18 — the year after demonetisation and the one that saw the introduction of GST. Then in 2019 came the news that between 2012 and 2018, the total number of employed people fell by 9 million — the first such instance of total employment declining in independent India’s history.

As against the norm of an unemployment rate of 2%-3%, India started routinely witnessing unemployment rates close to 6%-7% in the years leading up to Covid-19. The pandemic, of course, made matters considerably worse.

What makes India’s unemployment even more worrisome is the fact that this is happening even when the labour force participation rate — which maps the proportion of people who even look for a job — has been falling.

With weak growth prospects, unemployment is likely to be the biggest headache for the government in the remainder of its current term.

Inflation rate

In the first three years, the government greatly benefited from very low crude oil prices. After staying close to the $110-a-barrel mark throughout 2011 to 2014, oil prices (India basket) fell rapidly to just $85 in 2015 and further to below (or around) $50 in 2017 and 2018.

On the one hand, the sudden and sharp fall in oil prices allowed the government to completely tame the high retail inflation in the country, while on the other, it allowed the government to collect additional taxes on fuel.

But since the last quarter of 2019, India has been facing persistently high retail inflation. Even the demand destruction due to lockdowns induced by Covid-19 in 2020 could not extinguish the inflationary surge. India was one of few countries — among comparable advanced and emerging market economies — that has witnessed inflation trending consistently above or near the RBI’s threshold since late 2019.

Going forward, inflation is a big worry for India. It is for this reason that the RBI is expected to avoid cutting interest rates (despite faltering growth) in its upcoming credit policy review on June 4.

Fiscal deficit

The fiscal deficit is essentially a marker of the health of government finances and tracks the amount of money that a government has to borrow from the market to meet its expenses.

Typically, there are two downsides of excessive borrowing. One, government borrowings reduce the investible funds available for the private businesses to borrow (this is called “crowding out the private sector”); this also drives up the price (that is, the interest rate) for such loans.

Two, additional borrowings increase the overall debt that the government has to repay. Higher debt levels imply a higher proportion of government taxes going to pay back past loans. For the same reason, higher levels of debt also imply a higher level of taxes.

On paper, India’s fiscal deficit levels were just a tad more than the norms set, but, in reality, even before Covid-19, it was an open secret that the fiscal deficit was far more than what the government publicly stated. In the Union Budget for the current financial year, the government conceded that it had been underreporting the fiscal deficit by almost 2% of India’s GDP.

Rupee vs dollar

The exchange rate of the domestic currency with the US dollar is a robust metric to capture the relative strength of the economy. A US dollar was worth Rs 59 when the government took charge in 2014. Seven years later, it is closer to Rs 73. The relative weakness of the rupee reflects the reduced purchasing power of the Indian currency.

These were some, not all, of the metrics that often qualify as the fundamentals of an economy.

What’s the outlook on growth?

The biggest engine for growth in India is the expenditure by common people in their private capacity. This “demand” for goods accounts for 55% of all GDP. In Chart 3, the blue curve shows the per capita level of this private consumption expenditure, which has fallen to levels last seen in 2016-17. This means if the government does not help, India’s GDP may not revert to the pre-Covid trajectory for several years to come. It is for this reason that the latest GDP should not be viewed as an outlier.

Explained: India’s GDP fall, in perspective - The Indian Express

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment